2022年9月3日 星期六

進擊的阿北-Yamaha EC-05電動機車試駕報告-(2)產業篇

A wild hog’s test-ride of Yamaha EC-05 e-scooter - (2) industrial insight

試車題外話1:為什麼EC-05賣的這麼差?

(1) 通路面:電動機車的維修保養比油車簡單便宜,遇到電系故障技師也沒有甚麼維修技術施展的空間,這對於現有傳統(油車)機車經銷商的生存是很不利的。

所以像Yamaha這樣龐大的傳統品牌經銷通路,經銷商主推油車、輕縱電動機車買家,是很現實的狀況。電動車(包含電動機車)需要發展一套從製造、銷售、保養維修的環節均能讓體系內廠商獲利的模式,經銷商們才願意努力銷售。其實,例如政府政策開放合理的改裝,可能是一種解方。(2)

市場面:電動機車目前價格高出油車5成、又騎不遠,所以市場的基本盤以小巧便宜車款、短程使用、女性用戶為大宗。EC-05專營高性能、大尺碼、高單價的市場,在電動機車當然很難吃的開。

(3) 行銷面:初代EC-05其實是Gogoro2S性能版(7.6 kW 10.3 ps,),基礎牌價就是10萬元的水準,再搭配1萬元配件金的店頭促銷。但是零廣告零溝通的販售方法,很難讓消費者對EC-05產生詢問的興趣,反而促進購買Gogoro車款、或是產品特色爆點吸睛的宏佳騰車款的合理性。2022年四月起EC-05的馬達改用Gogoro22的7.0 kW 9.5 ps一般版,售價全面調降9千~1.1萬元。

(4)

產品面:就是一部男人(騎姿較高)在騎的車。雄壯威武、高大重,但偏偏比較貴又騎不快,這在消費者口碑傳播方面就很傷了。

試車題外話2:為什麼市場龍頭光陽的電動機車賣得跟EC-05差不多?

(1)

通路面是最大的課題,這個部分光陽與台灣山葉都面臨相同的挑戰。

(2)

就短期來看,光陽為了維持台灣市場霸主地位而堅持開發自己的電力供應(換電+充電)系統。換電站網路便利性在創業初期當然很難與Gogoro Network抗衡比較,買氣萬人響應一人買單是蠻必經必然的。

(3) 就產品研發策略來看,光陽有踩雷觸犯幾個較大型的失誤:主要是急於創造產品差異化與規避先進者(睿能)專利,光陽想要在續航力領先而在初期(2018年)使用沉甸的電池(不適合女性操作,男性操作體驗也差),摸索了3年(至2021年)還是回到與Gogoro Network近乎完全相同的21700電池蕊/10公斤規格的電池模組;90度垂直壁掛電池架(Gogoro Network的20度傾角取放方式,較符合人體工學);率先採用2檔變速箱(這真是很有膽識的好嘗試,業界實證之後發現在電動機車、甚至300匹馬力之內的電動車都沒用,雖然失敗但仍然應該給予掌聲鼓勵);車輛空重比同級競爭對手硬是少掉了5~10公斤(公開資料尚看不到例如鋁合金零件等技術的使用,產品安全性堪慮)等等……。光陽必須要提供更好的解決方案,才能逐漸累績消費者興趣與信任,放心買單。

電動機車入坑建議準則

換電式電動機車好看、好玩、好騎、環保(至少表面上看起來是這樣)、又好照顧,但是車價好貴(即使把購車補助算下去也是)、騎不遠、又有坑人的月租費。怎樣才是掏錢成為換電式電動機車車主的好時機?我認為有幾個簡單的原則可以來協助判斷:

(1)

離家1公里內有換電站。(來回換電站的距離、時間才是最惱人的成本)

(2)

要有穩定的騎乘使用需求。(太多天放著不騎容易當機、興致一來騎長途要繳超額里程資費、愛騎不騎看到月租費帳單就會抱怨)

(3)

日常的單日通勤里程<40公里。(只要時常會擔心該換電池了,那換電式電動機車就不適合您)

(4)

住家最好位於市區。(只要是通勤距離里程長、住家附近沒有換電站,那還是騎油車合適)

(5)

要有保用持有5年以上的盤算把握。(充電式電動機車目前市佔率仍低,中古車接手買氣更低;過戶很麻煩,有機車、電池、個人帳戶要在廠商的系統伺服器裡辦理轉移,交易超容易卡關。騎個一~二年就賣,價格保證讓您捶心肝)

(6)

如果你喜愛飆車,又超有自信不會A到,那電動機車就不適合你。(電動機車同時具備速克達大面積塑膠件多、電動車動力馬達與控制元件只能換不能修的缺點,中度以上毀損的修理費用至少都是3分之1車價起跳,帳單會讓你後悔買車)

以上6個重點考慮清楚了,買(或不買)換電式電動機車就會是很愉快的事。

怎樣看待電動機車退坑群與黑特族的評價?

網路世界的達人、女神、幹譙龍很多,關鍵字隨便打就有好幾支電動機車退坑的黑特影片也是很當然的事。影片的內容劇情五花八門,不過歸納起來的情境大抵都是這樣:

(1)

搬家或是生活動線改變,換電不再方便。

(2)

車子少騎,多是臨時有需要才重度使用,對於月租費其實很感冒。

(3)

有犁田或是撞車過,修理費帳單嚇人,所以退坑之餘還要拍片分享讓大家知道。

(4) 車子修不好,機車行老闆與師傅搞不定又不友善。關於這一點,因為電動機車的品牌與車款眾多,我自己只擁有過EC-05而且沒遇過不好的維修經驗,所以沒有甚麼立場來評論。

關於Gogoro Network的電池與換電系統

雖然說睿能Gogoro的企業文化有不少地方讓人感冒,但是創業者與其公司發展出來的電池交換系統、以及為了賣電來投注研發的電動機車,經過7年來的市場考驗,我們可以厚著臉皮沾光的說:這家企業的產品與經營模式,已經將電動機車、甚至電動汽車的發展路徑確立了明確地圖:也就是機車走換電系統、汽車走快速充電系統、重型機車(30匹馬力以上)可由製造廠自選規格。不只是我們台灣的政策可以安心長期發展佈建,也很適合大部分的國家來仿效,所以可以說是另一個台灣之光。主要的關鍵是:

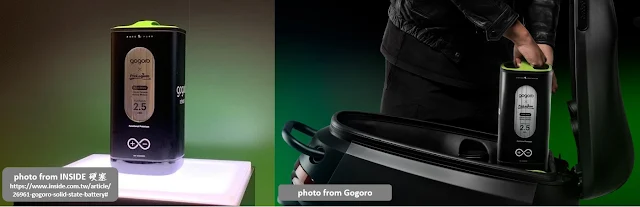

(1) 電池的發展:僅七年的時間,Gogoro Network的電池已經歷經3次的升級,分別是第1代的Panosonic 18650電池、第1.5代的LG 18650電池、第2代的Panasonic 21700電池。除了安全無虞、電池容量漸次提升了約25%、顯然還有繼續提升的空間(第3代固態電池原型已經發表),最要緊的是使用者端、供電端(電網)業者、產品(機車)製造商都沒有影響。核心的供電產品更新變化不會牽動到基礎建設的改變,容許各式規模的上下游業者生存與發展,這種多贏的模式對國家社會非常有利。

(2)

使用者的便利:機車採用換電只需20秒不到的時間,比加油還快,解決了充電式加電設備在尖峰時間一定會面臨的塞車缺電問題;電池重量與型式可以讓消費者輕鬆無腦操作,封閉式系統設計可阻止用戶移作不當用途釀成公共危險事件。這是比油車的加油站還棒的模式,社會得利。電動汽車所需電能功率太大(依目前發展來看70 kWH會是主流,相較於主流電動機車僅需2個1.7 kWh的電池,差距20倍),消費者扛不動這樣的電池,所以無法採用換電模式(大陸本土汽車廠有發展換電式電動汽車,市場證明發展潛力有限),只能繼續朝超大功率(目前主流是100 kW,300 kW產品設備已上市營運,1000 kW的規格尚在測試階段)的快充發展,未來10年很有機會完成10分鐘內為電動汽車充電50%的產業通用型規格標準。總歸來說,機車與汽車在未來10年,仍然很難共用一套系統,而睿能幫全世界開發出一套非常好用的機車換電系統,這很優。

(3)

降低對其它產業的衝擊:一個產品、技術、或產業的創新,如果對其它產業產生大規模的取代淘汰效果,造成社會動盪失衡的代價是很驚人的。幾年以前Uber取代計程車產生的社會影響,大家應該還有些記憶。由於電動車產業不再使用內燃機,根據德國、日本政府的評估,會影響削減15%左右的工作機會。試想我們高興購入一部電動機車,但代價會是看到鄰居親友失業,機車行關門大吉,這通常不能算是好事。機車換電站、汽車快充站的模式有利於加油站業者能夠轉型繼續生存;換電、快充的大電流高電壓設備,都是危險且不利人體健康的嫌惡設施,不要進入家戶社區裡面其實對社會大眾更好;另外,大電流高電壓設備進入電網末端的低壓供電社區,不只供電配電風險大增,整個線路基礎設施要重挖重鋪,也是勞民傷財又動輒好幾年的事。睿能這個吃電胃口不大、模組可以彈性串接可小可大、又能讓現有加油站業者續命的換電經營模式,業者自己能賺錢,對於社會安定也有正向的作用。

電動機車產業的可能發展方向

(1)

台灣機車的內需市場一年有80~100萬輛的胃納量,產業業者的發展規模有機會具備國際級的競爭力,電動機車當然也包含在內,尤其是台灣業者的起步相對各國較快,體質尚佳。這比台灣只剩蓋滿10幾間晶圓廠的台積電當護國神山,應該聽起來讓人放心、有指望一些……

(2)

經過這幾年技術市場與消費市場的證明,電動機車採用電池交換模式充電是最好的營運方式且沒有之一。萬一的萬一真的搞錯了,換電模式轉型為充電式營運方式操作,轉型成本也不高;反之,充電模式轉換為換電模式是做不到的。技術發展的趨勢與答案已經很明顯又低風險,政府可以安心扮演較為清楚積極的角色。

(3)

電池、電網、機車,其實是3個產業,產業規模均夠大且術業各有專攻。有業者想要贏者全拿,這是商業自由我們不能反對,但是政府必須要維持開放競爭的產業環境,以維持產業創新進步的動能,並規避產業遭遇獨占、寡召形成的不公平競爭。

(4)

台灣機車市場規模容不下多家的換電系統,業者爭鳴對消費者的使用便利反而有妨害。像是到加油站想加中油、台朔、Shell、ELF都可以,這才是正解。

(5)

想要撐大產業規模讓業者有國際競爭力,又要維持產業內的開放競爭與進步,還要給社會大眾便利生活,政府可以嚴肅考慮設置規定電池尺寸規格與電流輸出輸入功率格式、電網設備規格與相容性安全性規範、機車的強制型泛用型充放電匯流管理與電網通訊協定等。使用者只需要面對一個電池交換電網(例如家裡電器只要是有插座就可用,但供電業者可能是台電、台塑、長生、台泥,供電來源有燃煤、燃氣、核能、水力、光電、風電等)。

(6)

由於產業發展的賽局已經很清楚,所以睿能必須至少拆分為2家公司,在電池交換電網的部分,開放機車與相關業者入股合資經營、公開發行不排斥國際資本介入、或是政府投資主導等方式都是可行,最重要的目的是在維持業者開放競爭的前提下,讓單一規格的換電系統可以在台灣發展出規模經濟,甚而有機會向國際市場輸出,這對於業者、社會大眾、政府均甚為有利。

(7)

整車業者的龍頭光陽、三陽、或是跨界的中華等眾家英雄好漢,在電動機車銷售歷史與規模均很小的初始階段、機車與設備的轉接過渡成本尚低的時候,使用這一套已經證明安全可靠、有機會藉用政府政策需要來爭取低價應用的換電系統,能專心又快速地在共通平台之上推出各式既成熟又容許創新的車款。

(8)

電池交換系統的規格化,除了讓機車業者更有誘因從油轉電華麗轉身,也加速達成政府降低碳排的目標;交換系統的電網本身除了既有的業主睿能、潤泰、政府投資等,還可以吸納重量級設備商台達電、中興電工,以及加油站、停車場等低階業者甚至能源商巨擘來參與投資或開外掛進場競爭。電池的部分產業趨勢更清楚,除了既有的業者,三陽發展中的鋁電池、台塑的磷酸鐵鋰電池事業、乃至於對岸的寧德時代都有機會讓我們的產業發展更迅速。

(9) 我們市井小民比較關心的還是機車好不好騎。從這幾年電動機車主流車款續航力50公里,累積銷量已達50萬輛,市佔率達3.5%來看,在車價不變(實際上更是緩慢下降)但第2代電池(21700)續航里程已經逼近100公里,如果三年內換電系統電池全數汰換完畢,電動機車市佔率達成5%是可以期待的。如果電動機車續航里程可達200公里,那麼燃油機車在台灣大概不用等到環保8期標準實施,新車銷售就會豬羊變色被消費市場淘汰了。續航200公里在十年內達成的機率很高,除了幾項高能量密度電池的技術都已經進入應用測試與投產評估的階段,在既有的主流速克達車身結構上,前方地板鞍部增加第3顆電池的設計空間也是可以合理期待的。

(10)

最後的題外話,機車可以用的這套換電系統,能不能出國比賽不知道(老實說我們國家業者不成材、政府被欺負的慘案實例比較多),但至少國內大家能用的很高興很方便。還可以合理期待的擴散效果,除了工業區內的無牌三輪、四輪物流車(已經至少有2款產品上市),還有各縣市農業區滿山遍野的農機、搬運車,這些恐怖噴煙烏賊可以洗白也是很棒的事。上述運輸工具、加上國內不好用但是業者外銷嚇嚇叫的ATV沙灘車等,基本上都是4顆電池以上的應用型式,也都是不錯的商品市場。唯獨電動自行車這一塊市場,除了真正的腳踏車衍生增程車款之外,其它根本就是速克達的電動自行車,我個人是比較傾向讓它們消失在地球上的。(雖然改起來超好玩)

希望藉由這一大篇幅的介紹,能讓更多人瞭解EC-05與換電式電動機車;也藉由這部有趣有料的機車產品,希望吸引更多人有興趣瞭解電動機車、乃至於電動車的產業現況與趨勢。

最重要的是:不要在紅綠燈前面與路邊停車找廁所時找我這個阿北問這部車哪裡買了! (^^)

延伸閱讀推薦

進擊的阿北-Yamaha EC-05電動機車試車報告-(1)產品篇https://seztwnscope01.blogspot.com/2022/08/yamaha-ec-05-1-wild-hogs-test-ride-of.html

Test-ride sidetalk 1:

Why are EC-05 sales so poor?

(1) Channel perspective: Electric scooters are easier and cheaper to maintain than gas-powered ones, and when it comes to electrical system failures, mechanics have limited repair options. This is detrimental to traditional (gas-powered) motorcycle dealerships. Hence, large traditional brands like Yamaha tend to promote gas-powered vehicles while downplaying electric scooters, which is a practical reality. For electric vehicles (including scooters) to succeed, a model needs to be developed where manufacturers, sales, and maintenance services can all profit from the system, prompting dealers to actively sell them. For example, opening up reasonable modification options through government policies might be a solution.

(2)

Market perspective: Currently,

electric scooters are priced 50% higher than gas-powered ones and have limited

range, so the core market is focused on small, affordable models for short

trips, primarily targeted at female users. The EC-05, being a high-performance,

large-sized, and high-priced model, struggles to find traction in this electric

scooter market.

(3) Marketing perspective: The first-generation EC-05 was essentially the performance version of the Gogoro 2S (7.6 kW, 10.3 ps), with a base price around NT$100,000, plus a store promotion offering NT$10,000 worth of accessories. However, selling it with zero advertising and no consumer engagement made it difficult to generate interest in the EC-05. Instead, it inadvertently boosted sales of Gogoro models or the eye-catching AEON models with distinct product features. Starting in April 2022, the EC-05 switched to the general version of the Gogoro 2’s 7.0 kW, 9.5 ps motor, with a price reduction of NT$9,000 to NT$11,000.

(4)

Product perspective: It's a bike

primarily for men (with a higher riding position). It looks strong and

imposing, but it's relatively expensive and not particularly fast, which hurts

word-of-mouth among consumers.

Test-ride sidetalk 2:

Why are KYMCO’s electric scooter sales as poor as the EC-05’s, despite being

the market leader?

(1)

Channel perspective: This is the

biggest challenge, and KYMCO faces the same issues as Yamaha Taiwan.

(2)

Short-term outlook: KYMCO, in order to

maintain its dominant position in the Taiwan market, insists on developing its

own power system (both battery swapping and charging). Naturally, in the early

stages of building a battery swap station network, it’s hard to compete with

the convenience of the Gogoro Network. The market's response has been one of

"thousands responding, but only one purchasing," which is an

inevitable phase.

(3) Product development strategy: KYMCO made several significant mistakes in its rush to differentiate its products and avoid infringing on the advanced patents of Gogoro. Initially (in 2018), KYMCO used heavy batteries to lead in range (unsuitable for women, and even men found it a poor experience). After three years (by 2021), KYMCO had to revert to using nearly the same battery modules as Gogoro, with the 21700 battery cell and a 10 kg battery pack. Additionally, KYMCO adopted a vertical 90-degree battery rack (compared to Gogoro’s 20-degree angle, which is more ergonomic), and boldly introduced a two-speed transmission. Though this was a courageous and worthy attempt, the industry later proved it was unnecessary for electric scooters or even electric cars with up to 300 hp. Despite its failure, KYMCO deserves applause for trying. Furthermore, KYMCO’s vehicles are 5-10 kg lighter than its competitors in the same class (public data does not yet show the use of technologies like aluminum parts, raising safety concerns). KYMCO must offer better solutions to gradually build consumer interest and trust, encouraging more confident purchases.

Guidelines for entering

the electric scooter market

Battery-swapping

electric scooters are stylish, fun to ride, eco-friendly (at least on the

surface), and easy to maintain. However, they are expensive (even with

subsidies), have limited range, and come with a burdensome monthly subscription

fee. So, when is the right time to invest in one? I believe the following

simple principles can help guide your decision:

(1)

You live within 1 km of a battery swap

station (the time and distance to the station is the most annoying cost).

(2)

You have stable daily usage needs

(letting it sit too long may cause malfunctions, and long-distance rides will

incur extra mileage fees, while inconsistent riding habits can lead to

frustration when you see the monthly subscription bill).

(3)

Your daily commute is under 40 km (if

you're constantly worried about needing a battery swap, a battery-swapping

electric scooter is not for you).

(4)

You live in the city (if your commute

is long and there are no swap stations nearby, sticking with a gas-powered

vehicle is more suitable).

(5)

You plan to own it for over 5 years

(battery-charging scooters currently have a low market share, and resale demand

is even lower. Transferring ownership is complicated, requiring you to handle

the vehicle, battery, and personal account transfer within the manufacturer’s

system, which can easily cause transaction delays. If you plan to sell it after

one or two years, you’ll regret it when you see the low resale price).

(6)

If you love speeding and are confident

you won't crash, electric scooters aren't for you (electric scooters combine

the downside of large plastic body panels common in scooters with the fact that

electric motors and control units can only be replaced, not repaired. Repairing

moderate or severe damage will cost at least one-third of the vehicle’s price,

leaving you with a bill that makes you regret your purchase).

Once

you've thoroughly considered these six points, deciding whether to buy a

battery-swapping electric scooter will be a joyful experience.

How to value the

opinions of those quitting electric scooters and the haters?

The

internet is full of experts, influencers, and angry rants, so it's no surprise

that a search for electric scooter "quitting" videos will yield a

good number of hater content. These videos cover a wide range of scenarios, but

the situations can generally be summarized as follows:

(1)

They moved or their lifestyle changed,

making battery swapping less convenient.

(2)

They rarely ride the scooter and

mainly use it heavily only when needed, which makes them resent the monthly

subscription fees.

(3)

They've had accidents or crashes, and

the repair bills were frightening, prompting them to make videos to warn others

after quitting.

(4)

Their scooter couldn't be properly

repaired, and the shop owners and mechanics were unhelpful and unfriendly. On

this point, since there are many brands and models of electric scooters, I’ve

only owned an EC-05 and never had a bad repair experience, so I don’t have much

of a stance to comment on this.

About Gogoro Network’s

battery and swapping system

While

there are several aspects of Gogoro’s corporate culture that people find

irritating, the battery swapping system developed by the founders and their

company, as well as their investment in electric scooter R&D for battery

sales, have been market-tested over the past seven years. We can confidently

say that their products and business model have charted a clear path for the

development of electric scooters and even electric cars. This path includes

battery swapping systems for scooters, fast charging systems for cars, and

heavy motorcycles (with over 30 horsepower) allowing manufacturers to choose

their own specifications. Not only can Taiwan safely develop long-term policies

based on this, but it’s also a model other countries can adopt, making it another

proud achievement for Taiwan. The key points are:

(1) Battery development: In just seven years, Gogoro Network’s batteries have undergone three upgrades: the 1st generation Panasonic 18650 battery, the 1.5 generation LG 18650 battery, and the 2nd generation Panasonic 21700 battery. Besides being safe, the battery capacity has gradually increased by about 25%, with room for further improvement (the prototype of the 3rd generation solid-state battery has already been unveiled). The most important aspect is that these upgrades have not impacted users, the power supply network, or manufacturers. The core power product updates don’t require changes to the underlying infrastructure, allowing businesses of all sizes in the supply chain to survive and grow. This multi-win model benefits the nation and society.

(2)

User convenience: Swapping

a scooter’s battery takes less than 20 seconds, faster than refueling a

gas-powered vehicle, solving the congestion and power shortage issues that

would arise during peak hours with charging stations. The battery’s weight and

design make it easy for consumers to handle, and the closed system prevents

users from repurposing it for unsafe activities that could pose public risks.

This model surpasses gas stations and benefits society. As for electric cars,

the power required is too great (current developments suggest that 70 kWh will

be the standard, compared to the 1.7 kWh batteries that most electric scooters

use, a 20-fold difference), and consumers can’t handle such heavy batteries,

making battery swapping impractical. (Although some Chinese automakers have

tried swapping batteries in electric cars, the market has shown limited

potential for this.) Instead, the focus will continue to be on ultra-high-power

fast charging (currently, 100 kW is the standard, 300 kW products are already

in operation, and 1000 kW standards are still in testing). Over the next

decade, there’s a good chance that industry-wide standards will be established,

allowing for electric car batteries to charge 50% in under 10 minutes. Overall,

for the next 10 years, scooters and cars will struggle to share the same

system, and Gogoro has developed an excellent battery-swapping system for

scooters globally, which is impressive.

(3)

Reducing impact on other industries: When

a product, technology, or industry innovation leads to the large-scale

replacement or elimination of other industries, the resulting social

instability and imbalance can be costly. Many people still remember the social

impact caused by Uber replacing taxis a few years ago. The electric vehicle

industry no longer relies on internal combustion engines, and governments in

Germany and Japan estimate that it will reduce employment by about 15%. Imagine

buying an electric scooter and being excited about it, only to see your

neighbors or relatives lose their jobs, or the local mechanic’s shop close

down. This is typically not a good outcome. The battery-swapping stations for

scooters and the fast-charging stations for cars allow gas station operators to

transition and continue operating. Battery swapping and fast charging involve

high-current, high-voltage equipment, which can be dangerous and harmful to

health, so it’s better to keep them out of residential communities.

Additionally, introducing such equipment into the low-voltage areas of the

power grid at the end-user level would greatly increase risks, requiring a

complete overhaul of the electrical infrastructure, which is costly and

time-consuming, potentially taking years. Gogoro’s battery-swapping model, with

its moderate power demand, flexible modular design, and ability to scale from

small to large, allows existing gas station operators to continue their

business. This model enables businesses to make a profit and contributes

positively to social stability.

Possible development directions

for the electric scooter industry

(1)

Taiwan's domestic scooter market has a

capacity of 800,000 to 1 million units annually, giving the industry the

potential to develop international-level competitiveness. Electric scooters are

naturally included in this, especially since Taiwanese companies have had a

relatively faster start compared to other countries and are in good shape. This

should be more reassuring and hopeful than relying solely on TSMC, with its

dozen or so fabs, as Taiwan’s national guardian.

(2)

Over the past few years, both the

technology and consumer markets have proven that using a battery-swapping

system for electric scooters is the best operational model, without exception.

If, by some chance, this turns out to be wrong, switching from battery swapping

to a charging model has low transition costs. On the contrary, transforming

from a charging model to a battery-swapping system is nearly impossible. The

trends and answers to technological development are already clear and low-risk,

allowing the government to play a more proactive and confident role.

(3)

Batteries, power grids, and scooters

are essentially three separate industries, each large enough and specialized in

its own field. While some companies aim to dominate the entire market, this is

part of business freedom, and we can't oppose it. However, the government must

maintain an open and competitive industrial environment to ensure continued

innovation and progress, while avoiding monopolies and unfair competition.

(4)

Taiwan's scooter market isn't large

enough to support multiple battery-swapping systems. Competition among

operators could hinder user convenience. For example, at a gas station, you can

choose to fill up with CPC, Formosa, Shell, or ELF fuel—this is the ideal

model.

(5)

To scale the industry, give businesses

international competitiveness, maintain open competition and innovation, and

provide convenience for society, the government could seriously consider

standardizing battery sizes, input/output power formats, power grid

specifications, safety regulations, and universal charging management

protocols. Users should only need to interact with a single battery-swapping

grid (similar to how any home appliance can be plugged into a socket, but the

power provider might be Taipower, Formosa, Chang Sheng, or Taiwan Cement, with

the energy source being coal, gas, nuclear, hydroelectric, solar, or wind

power).

(6)

Since the industry's development

trajectory is clear, Gogoro should consider splitting into at least two

companies. The battery-swapping grid could open up to joint ventures with

scooter and related companies, issue public stock, welcome international capital,

or even have government-led investments. The most important goal is to maintain

open competition, allowing a single standardized battery-swapping system to

achieve economies of scale in Taiwan, and possibly expand internationally,

benefiting businesses, the public, and the government.

(7)

Major players in the complete scooter

industry, like Kymco, SYM, or even cross-industry companies like Chunghwa,

should seize the opportunity during the early stages of electric scooter

development when the market is still small, and transition costs for scooters

and equipment are still low. They could utilize this proven safe and reliable

battery-swapping system, which could also gain government support for low-cost

applications, and quickly introduce various innovative and mature models on a

common platform.

(8)

Standardizing the battery-swapping

system not only incentivizes scooter manufacturers to transition from fuel to

electric smoothly but also accelerates the government's carbon reduction goals.

The battery-swapping grid, apart from its current operators like Gogoro,

Ruentex, and government investors, could attract heavyweight equipment

companies like Delta Electronics and Chung Hsing Electric to invest, as well as

lower-tier operators like gas stations, parking lots, and even energy giants to

join in or compete. As for the battery industry, the trend is becoming even

clearer, with opportunities for SYM’s development of aluminum batteries,

Formosa’s lithium iron phosphate battery ventures, and even China's CATL to

accelerate the growth of our industry.

(9) The public is more concerned about whether the scooters are enjoyable to ride. Looking at the mainstream electric scooters over the past few years, with a range of 50 kilometers and total sales reaching 500,000 units, capturing 3.5% of the market, the second-generation 21700 battery now pushes the range to nearly 100 kilometers, all while prices remain steady (and even slightly decreasing). If the entire battery-swapping system is upgraded within three years, a market share of 5% for electric scooters is achievable. If electric scooters can reach a range of 200 kilometers, then fuel scooters might be phased out by the consumer market before Taiwan’s Stage 8 environmental standards even take effect. Achieving a 200-kilometer range within the next 10 years seems highly probable, not only because high-energy-density battery technologies are entering the testing and production stages, but also because it’s reasonable to expect room for a third battery in the footwell area of existing mainstream scooter designs.

(10)

A side note: It’s uncertain whether

this battery-swapping system could compete internationally (to be honest,

Taiwan’s businesses often lack international success, and the government has

frequently been mistreated), but at least domestically, it’s convenient and

popular. One could reasonably expect this system to expand to unlicensed three-

and four-wheel logistics vehicles in industrial areas (there are already at

least two products on the market) and agricultural vehicles in rural areas.

Cleaning up the pollution from these smoky "octopuses" would be

fantastic. Moreover, ATVs, which don’t sell well domestically but are a hot

export item, typically use four or more batteries, making them another good

product market. However, the electric bicycle segment, except for true

pedal-assisted models, is essentially just electric scooters in disguise.

Personally, I’d prefer to see them disappear from the planet (although they are

a lot of fun to modify).

Hopefully,

this lengthy introduction will help more people understand the EC-05 and

battery-swapping electric scooters. And through this interesting and

informative scooter, I hope to attract more people to learn about the current

state and trends of the electric scooter and electric vehicle industries.

Most importantly: Don’t ask me where to buy this scooter when you see me at a red light or parked on the roadside looking for a restroom! (^^)

Further reading recommendation:

沒有留言:

張貼留言